Vignettes of Champion Hill By "To hear the call of the whippoorwill is a sound that, for me, epitomized the loneliness of the Champion Hill battlefield."

click here for Click on the audio icon to hear Margie read selected vignettes.

Small night noises began to invade the deep silence over the Champion Hill battlefield. The raucous cricket’s noise blended with the encroaching dark. From Bakers Creek the little rain frogs called occasionally. The day’s sunshine revealed sharp clear images of rocks, trees, and fields - the remains of a hillside that once claimed so many dead. I felt the backward zoom of time - back to when blue and gray-clad ghosts struggled in a life and death fight. The fields and ravines are now desolate and empty of everything except the spirits of those who died - Yankees and Rebels - all heroes - both fighting for what they believed and held so dear. The sun dipped below the horizon and I gazed outward over the battlefield as the lingering shades of daylight gave way to total darkness. Then, I listened as the night music swelled into a symphony of sound.

Years later, after I met and married Ed Bearss who at the time was the historian at the Vicksburg National Military Park, we visited Champion Hill where Ed was checking out the battlefield sites and drawing maps. The upper section of the crossroads had been opened and was passable from the site of the Champion house to the crossroads. I was amazed at how near the crest of Champion Hill was to the crossroads and to the upper section of the old Jackson Road. That stretch of road has now been closed for years. As Ed and I climbed the side of the hill, I began to feel uneasy and apprehensive. Too many men had died in the various charges on this hill. It was a solemn place of death. As I reached the top, my hair stood out from the back of my neck and my arms broke out in chill bumps. I could almost feel the menace of the Yankee charge breaking across the field. I have never since felt such unease and apprehension on the hill.

The air was chilly and the water even cooler as I waded

into the debris around the Charm. The river was low - knee deep in

spots - and at one spot only ankle deep - and the engine could be seen.

The ruins were lying horizontally so one could walk from end to end.

To hear the call of the whippoorwill is a sound that, for me, epitomized the loneliness of the Champion Hill battlefield. The haunting call evoked powerful feelings for a battlefield that once was so full of life and is now only a memory of the dead. It was getting late - dusk was falling and Ed was talking to Sid III. I was waiting at the car for Ed and all was quiet - except for the cricket’s night noise. Suddenly, the silence of the night was interrupted by the distant ragged sound of a whippoorwill’s call. At first I believed it was my imagination. The lonely call fit so perfectly into the picture. About that time from a nearby grove of trees came the answering call of another whippoorwill - loud and clear. Chills went up my spine. The whippoorwill’s call over the darkening battlefield was a sound that I will never forget.

Cistern Quenches Soldiers Thirst

May 16th dragged on endlessly. The light was beginning to fade - the Confederates were withdrawing and heading for the crossing of Big Black on their retreat to Vicksburg. The day had been hot but it seemed airless because of the cannon smoke that had seeped over the hill and lay heavily around the Cook house which had borne so many charges and counter charges across the Hill of Death. Dozens of wounded - both Yankee and Confederate - were scattered over the yard as well as the dead. The cistern beside the Cook house held water which appeared almost as a miracle to the men with parched dry throats. They drank and filled their canteens. This cistern had been built in the 1830’s by Lazarus Cook about the time he started his family. Seventeen children were born to Lazarus and Adeline (Addy) and the cistern was in constant use. During the battle, the Cooks had stayed in the house - the older boys, Greenberry, James, and John were away fighting but the rest of the family stayed though the house was riddled with Minnie balls. In 1962, the supporting sills still had Minnie’s embedded in them. What a shame the sills were replaced with brick. For almost a century and a half, the Cooks' cistern has stood sentinel over a section of the battlefield that saw heavy fighting. Now, a few of its bricks are crumbling but its presence reminds us of the soldiers, blue and gray, who quenched their thirst from the well during the heat of battle. The Cooks' cistern is a visual part of the Champion Hill battlefield’s heritage. Hopefully, the antebellum site will be preserved for future generations of tourists as they explore the battlefield where Grant and Pemberton engaged in the bloodiest battle of the campaign for Vicksburg.

Out of the Mists: The Champion House

In the musical Brigadoon the little village appeared out of the mists of time once every hundred years. So out of the mists of time, on November 12, 2005, on Champion Hill, Matilda’s house appeared very much alive. A light wind made the flags blow as the autumn leaves slowly fell. People gathered to hear the dedication of the book My Dear Wife: Letters to Matilda - The Civil War Letters of Sid and Matilda Champion - a book dedicated to the Southern heroine Matilda Champion. These were the war time letters between Sid S. Champion (a member of the 28th Miss Cavalry) and his wife, Matilda, who stayed at home during the early stages of the war. Her house was later torched by the Union soldiers and she was left to fend for herself and four small children. Matilda’s second home had settled into the fog of obscurity but on November 12, 2005, it was filled with people happy to pay tribute to a genuine heroine. A dozen red roses on her grave (she loved roses) and a Confederate flag behind her husband’s grave added to the feeling that Sid and Matilda were watching and enjoying the occasion. At the refreshment table were miniature buttermilk pies made from Matilda’s recipe that she had slipped between the pages of a favorite book. The day was bright with sunshine as the crowd mingled on the grounds of Matilda’s once beloved home - all enjoying the music and the ambiance of the day while viewing the family treasures that appeared out of the mists of time.

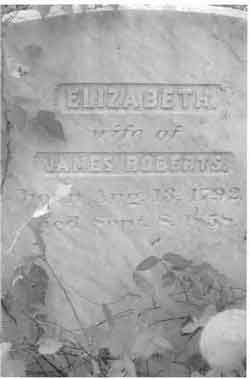

The Roberts Family Cemetery at Champion Hill

In 1936, my uncle Robbins Riddle owned a school bus. One Saturday he took

a group of us, including his wife, Lemly Cook Riddle, and two of her

siblings, Carolyn and Ray Cook, to Champion Hill to visit Lemly’s

grandfather, Stephen Lazarus Cook. Stephen was the youngest son of Lazarus

Cook whose house was located near the crossroads at Champion Hill.

During the 1960s, after marrying Ed, I learned that there was an old cemetery behind the James Roberts house. It seemed logical to me that Lazarus and Adeline would be buried in her father’s cemetery. We went to look. We found the cemetery in very bad shape - big trees pushing over the gravestones, heavy underbrush and broken stones. It was unkempt and too overgrown to explore. For the time being I gave up on finding Lazarus and Addie. Several years passed before Ed and I visited the Robert’s Cemetery again. I could not believe my eyes. Some men cutting timber had cut the big trees and cleared out the underbrush. The headstones had been piled along the fence row in heaps. Without the headstone, I could not tell where the graves were - although a few had sunken a bit. I gave up and abandoned the hope of finding the grave site of Lazarus and Addie Cook. In recent years, Ed visited the cemetery and reported that it was clean and that the stones were back in place. Whether or not they are in the same place as they were previously we’ll never know.

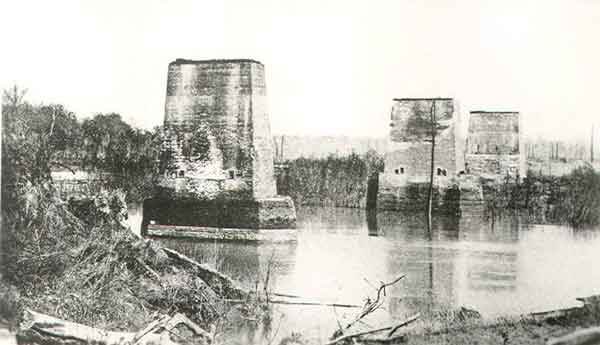

Discovering the Ruins of the "CSS Charm" & "CSS Paul Jones"

Charm, a side wheeler of 223 tons, served heroically evacuating the wounded across the river at the Battle of Belmont, under heavy enemy fire. She also took the big guns to Grand Gulf. Paul Jones, a side wheeler of 353 tons, served as a transport was active in the effort to save Vicksburg. After Admiral David Porter ran the Vicksburg Batteries in April 1863, Paul Jones and Charm sailed up the Big Black River seeking refuge from the powerful Yankee fleet. The Big Black bridge was head of navigation in the Big Black River and - as fate would have it - the end of the line for the three gallant steamboats.

On May 16, 1863, following the Battle of

Champion Hill, the defeated Confederates, with the Yankees in hot pursuit,

moved toward the boat and railroad bridges over the Big Black River. The

Confederates had positioned the steamer, Dot, “fore and aft across

the river” to serve as a makeshift bridge while the Charm and

Paul Jones

were anchored athwart the stream, lashed together. On May 17, the

Confederates dumped barrels of turpentine on the decks then set them

ablaze so they couldn’t be taken by the Yankees. The Dot, Charm and Paul Jones

burned to the water line.

Today, I have in my possession a 1960’s scrapbook containing all of the data associated with the finding of the Charm and the Paul Jones. The scrapbook, one of my prized possessions, contains not only photographs of the Charm’s ruins but also letters from many naval historians across America who took a great interest in the remains of these Civil War boats and the relics that were pulled from amidst the ruin. <click here to see Margie's Scrapbook>

Mystery of the "Dot" Where Did She Come from? Where Did she go?

In 1962, when Charm was found, I read all of the available records and diary entries that also named Paul Jones and Dot as victims of the Rebel defeat at Champion Hill. All three steamers met their demise near the railroad crossing of the Big Black River at Bovina. During the retreat from the battlefield at Champion Hill, Paul Jones had been lashed to Charm. Where was it now? There was no extra debris around Charm - no extra parts. I prowled the river bank. Ed and Col. Hanisee covered the river banks (both sides) with a mine detector. No luck. Also, where was Dot? It should I thought be the easiest to find. It had been anchored approximately 800 feet south of the railroad bridge. Pemberton in his after action report states that she had previously been stripped of her machinery and was used as a bridge for crossing soldiers. Dot was a tiny stern wheeler - much smaller than Charm. Her wreckage should have been nearby, but, if it was there, I couldn’t find it. The Dot intrigued me - not like the Charm which you could see and touch - but as an elusive “will of the wisp” that always seemed just out of reach. I went back to check Lytles List - an almost complete record of steamboats on the river until 1868. I found no mention of Dot - and none of the steamboat experts knew her dimensions much less where or when she was built. She seemingly appeared out of nowhere on the Big Black River - just in time to link her tragic fate to the Charm and Paul Jones. But what became of her? Since she was not weighed down by machinery had her charred remains been swept down river in high water? Could her remains have been scattered when the ruins of the bridge were cleared? In 1965, a land owner near along the Big Black River called to say the river bank had caved in, exposing part of what she thought was the Paul Jones. The ruins were found under the river bank - not under water…..showing scattered pieces - the Pittman strap, a hog brace, assorted iron pieces and a big piece of charred wood. It had to be the Paul Jones. Still, the mystery remains about Dot. Where did she come from? Where did she go?

Brandishing a Fire Poker

When Ed was researching his first book, Decision in Mississippi, he checked out some of the sites at Champion Hill, matching the houses to the Civil War maps. While at Champion Hill, he interviewed my Aunt Lemly Cook Riddle who was born in the Cook House near the Crossroads where her family had lived for several generations. Before the Battle of Champion Hill, the Champions went to Madison County but the Cooks stayed in their house during the battle, as did the Isaac Roberts family. The Cook house survived the vicious charges of the Union and Confederate forces but was riddled with bullets. During the interview, Aunt Lemly told us the following story: “After the battle the Confederates retreated to Vicksburg while the Yankee soldiers paused a while to rest. Nancy Cook, the seventeen-year-old daughter of Lazarus and Adeline Cook, saw the blue-clad soldiers scatter over the yards catching chickens and wringing their necks, preparing to make their supper. The Yankees spotted the smoke house and made a dash for it but Nancy was quicker. She grabbed the fire poker and dashed to the smoke house door. Standing with her back to the door she brandished the fire poker and declared that she would knock the brains out of the first Yankee who touched the doors to the smoke house. Surprisingly enough, the Yankees left and the hams in the smoke house were safe.” Aunt Lemly said that as long as Nancy lived her ‘kin’ teased her about running off the Yankees with a fire poker. During our visit, Lemly showed us where she and her siblings fished in Baker’s Creek, using Minié balls as sinkers for their fish lines. In the years after the war, the Cooks moved to the Hiawatha House on the Raymond-Edwards Road. Hiawatha and General Tilghman’s Death

The Daffodils of Champion Hill

Champion Hill

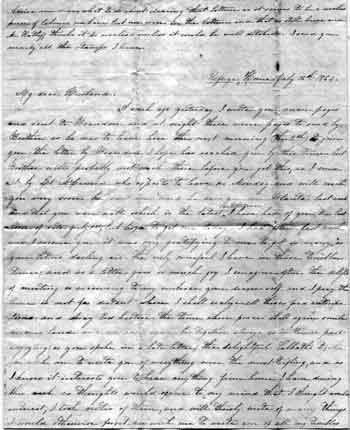

“Thanatopsis” After the turn of the century, Matilda Champion, widowed since 1868, lavished all of her attentions on her only grandson, Sid Champion III, the heir to Champion Hill. During his visits to grandmother’s house, Matilda taught him reading, writing, and arithmetic as well as literature and poetry. One of the poems that he studied and learned to quote before the age of nine was Thanatopsis - the central theme being that of death. Those who knew Sid III later in life knew that he loved to quote poetry and that Thanatopsis was one of his favorites: “So live, that when thy summons comes to join the innumerable caravan which moves to that mysterious realm, where each shall take his chamber in the silent halls of death, Thou go not, like the quarry-slave at night, scourged to his dungeon, but, sustained and soothed by an unfaltering trust, approach they grave like one who wraps the drapery of his couch about him, and lies down to pleasant dreams.” Sid III was obviously much more than a farmer. He was a well educated man and had a vast knowledge of classical literature, a legacy given to him by his grandmother. One has to wonder why Sid would have memorized a poem such as Thanatopsis whose central theme is death. Perhaps it had been one of Matilda’s favorites since for three years she had lived with the constant fear that Sid I would be killed during the war. But this did not happen. Instead, Sid returned from the war only to die three years later of a malignant fever. Around the same time, Matilda also lost her ten-year old son, Balfour, to an upper respiratory infection. The death toll continued to mount when in 1897, her youngest son, Sid II, died during the yellow fever epidemic that struck Edwards. Four years later, in 1901, her oldest son, Dr. Wallace Champion, died. Perhaps, in the face of so much death, Matilda found the thought of her loved ones “lying down to pleasant dreams” comforting. Many remember Sid III and his gift for quoting poetry, especially the final verse of Thanatopsis. Matilda’s Wartime Letters to Sid

Matilda was a strong and brave woman whose life is deserving of a book all her own. Even her grandson, Sid III, commented on the bravery of his grandmother’s life during such hard times: “The story of how Matilda, the woman who had been reared to be the Grand Dame, lived through reconstruction, reared her family and saved her land is one of fortitude and courage that surpassed anything that Sid had done in Vicksburg or in Georgia.” A few weeks after General Lee’s surrender, Sid wrote from his post in Alabama and requested that she make him a summer suit because he was being wined and dined in the homes of wealthy families in east Alabama. He wanted shiny boots and a new suit so he would look nice to his peers. Needless to say, Matilda didn’t make the suit. It thought it was time for her husband to leave the war behind and return home. Visiting the Hill of Death Years later, after I met and married Ed Bearss who at the time was the historian at the Vicksburg National Military Park, we visited Champion Hill where Ed was checking out the battlefield sites and drawing maps. The upper section of the crossroads had been opened and was passable from the site of the Champion house to the crossroads. I was amazed at how near the crest of Champion Hill was to the crossroads and to the upper section of the old Jackson Road. That stretch of road has now been closed for years. As Ed and I climbed the side of the hill, I began to feel uneasy and apprehensive. Too many men had died in the various charges on this hill. It was a solemn place of death. As I reached the top, my hair stood out from the back of my neck and my arms broke out in chill bumps. I could almost feel the menace of the Yankee charge breaking across the field. I have never since felt such unease and apprehension on the hill. Mural Depicted Gen. Francis Marion Cockrell at Champion Hill Shortly after I had the strange feelings about Hovey’s charge up Champion Hill, I started to wonder who was the target of the charge - Bowen’s countercharge I knew about but little else of the melee around the crest of the Hill. During the 1960s, I met Ken Parks, photographer and news producer for WLBT, who had grown up near Bolton and had explored Champion Hill since his childhood. He told Ed and me that he was painting a small mural of the charge Brigadier General Francis Marion Cockrell made trying to save the guns and hilltop. We visited Ken’s home to view the mural that depicted Gen. Cockrell riding up and down his line on his horse that was lathered with sweat. In one hand Cockrell waved his sword and in the other a magnolia blossom. He was pale and his dark hair flew in the air as he invigorated the Confederates. One end of the mural was finished and very good and the other end penciled in. In the excitement of raising the Cairo the little mural was forgotten and unfinished. However, in my imagination I can still see the impressive little mural of the heroic charge of Cockrell’s men.

The Battle Moves to the Big Black

When the guns ceased firing and darkness fell on May 16, 1863, many thought that was the end of the battle of Champion Hill. But the battle echoes kept rolling on as the weary outnumbered and defeated Confederates headed toward Vicksburg to regroup. In the dark of night, they attempted to make their way across the Big Black River bridge, eight miles west of the battlefield where men and vessels met their demise. A very potent image for me was the discovery of the wreckage of the Charm and Paul Jones in the Big Black river. During the Battle of Champion Hill, the vessels were anchored in the Big Black in the event they were needed. The defeated Confederates crossing the Big Black were still fighting to hold open the crossings. Many jumped into the river and crossed by swimming. How frightened the men must have been as they made the plunge from the steep and snaky banks of the river into the dark waters below. A few men drowned as the current swept them away. After the soldiers made the crossing and prepared to march for Vicksburg, they paused long enough to torch the Charm and Paul Jones to keep them from falling into enemy hands. During the 1960s, Ed identified the remains of the Charm which had been burned to the waterline athwart the river. Later, the ruins of Paul Jones appeared after a bank caved off and, in the process, exposed the century old treasure. As I viewed the ruins of the old vessel from the banks of the river, I realized the vessel’s demise, as well as Charm, represented the final moments of the Battle of Champion Hill. Finding a Carpet Bag As the defeated Confederates left the battlefield of Champion Hill, most were making a rapid passage across the Big Black River heading for Vicksburg. All the heavy accouterments seemed unnecessary so many “shucked their knapsacks,” cartridge boxes, and extra pieces of clothing on the bank before making the crossing - especially those who wanted to abandon the unnecessary weight before plunging into the swift swirling waters. More than a hundred years later, a young man using a mine detector near Charm and Paul Jones, the site where the soldiers went down the river bank to cross, dug up the rotting remains of a carpet bag. The metal frame of the bag attracted the mine detector. As the treasure was pulled from its century-old hiding place, the bag was found to have a cover of floral tapestry that was molded and crumbled at the touch. A carpet bag was a strange thing for a Confederate soldier to be carrying -or was it carried by a pursuing Yankee? Anyhow, after studying the contents of the bag, it was found to hold a straight razor, a cartridge tray of unused Miniés still in its wrapping (they were 58 caliber Gardners), and a decaying piece of what looked to be homespun cloth and had attached three white bone buttons (like the underwear buttons we found on Cairo. The most surprising article found in the bag was a Frozen Charlotte - a tiny porcelain doll which was pure white and looked like it was molded from snow. The doll was based on the legend of The Frozen Charlotte - a story of a young girl who died after riding to a New Year’s Eve ball in a sleigh with her sweetheart and refusing to dress warmly or use a blanket. Through the years, I've wondered who dropped the carpet bag and where the Frozen Charlotte came from. Frozen Charlotte Dolls

Most of the dolls were crudely painted yet some were pristine white. The doll found in the carpet bag buried on the banks of the Big Black River had no trace of paint. She was a lovely little Frozen Charlotte.

The Lazarus Cook House

Early Fascination with Minié Balls I fell in love with Champion Hill long before I ever saw it. I was a gawky 5th grader and my favorite Uncle Robbins Riddle married Lemly Cook, one of Lazarus Cook’s daughters. Lemly lived her childhood years in the battle scarred Cook House on the Champion Hill battlefield. One day, Lemly opened her trunk to remove something and while the trunk was open I spotted a small jar of Minié balls. I had never seen a Minié ball before. Lemly said they could be found all over the ground at Champion Hill and that her brothers often threw Minié balls at each other while playing. It was then I really realized the differences in Miniés - there were 3-ringers, 2-ringers or no ringers - and you could tell what type of gun fired what type of Minié ball. I reluctantly gave back the jar of Minié balls. So grew a two-pronged fascination - Champion Hill and Minié balls. Both interests have lasted 66 years and I see no abating of the interest.

Shortly after the turn of the century when Grover Cook was a boy, he found a pair of dueling pistols buried in the bank of Baker’s Creek. Were they the dueling pistols of General John Bowen that he lost during the Battle of Champion Hill a short time before his death? After the war, the Cooks moved from their house on the battlefield to the Hiawatha House on the Raymond-Edwards Road. Grover remembers taking the pistols with him when they moved. He kept the pistols for a number of years but in time could not remember what happened to them. Finding a Rebel Belt Buckle In the early 1970s while all four sections of the crossroads were open, Ed, with Sid Champion III’s permission, took a Civil War Round Table group on a tour. As they toured the battlefield, they came upon an old black man plowing a field. He had plowed up some relics and was quite willing to sell them. For quite some time I had wanted a Confederate belt buckle like my great grandfather wore in the 9th Alabama. However, the dealers’ prices were too steep - $100 to $200. There in the fields of Champion Hill lay a lovely Rebel belt buckle. Before Ed and I could react and make an offer, a man in the tour group grabbed the prized buckle and said, “I’ll give you $5.00 for it.” He did. The man plowing was happy. In fact, everybody was happy except me. I never did get a Confederate belt buckle in good shape. The Perfect Arrowhead

Explosive Miniés at Champion Hill Although three explosive Miniés had been picked up on the Vicksburg battlefield, both the Confederate and Union denied the use of explosive Miniés. It was true that the 2-ring Gardner explosives all looked like “drops.” One day in the early sixties there was an exciting find at Champion Hill! Ken Pasavantis found an explosive 32-pounder with an exploded shell casing. Snuggled inside the casing were numerous British experimental explosives with metal caps. Not a one had exploded. What a deadly shell if the inner Miniés had exploded! I was given one explosive and longed to see where the shell had landed but I never did - although we figured out on the maps that the impact area was probably where the 1st Mississippi Light Artillery had been firing shells. What a find! Explosives, yes. Explosives inside explosives, yes! Never again did I hear of anyone else making such a find. ‘Miss Ruth’ Champion

‘Miss Ruth’ Champion, wife of Sid III, was a lovely lady. In 1958 she took the time to talk to a group of my students. They loved her. She was a part of the Champion Hill story that went on long after the guns ceased firing on May 16, 1863. When we drove up to her house, two old ladies sat on the porch shelling peas. Now that I look back I realize that one of the ladies was ‘Miss Ruth’s’ mother-in-law, Olivia Champion Birdsong - the widow of Sid II. In 1897, after one year of marriage, Sid II died of yellow fever leaving Olivia pregnant with their first child. Sid III was born never having known his father. In later years Olivia married Dr. Birdsong, a local physician. While shelling peas, she told stories about some of the veterans, Union and Confederate, who visited Champion Hill long after the war. ‘Miss Ruth’ took us into the house to see some of Matilda’s furniture. She showed us the dining room table where amputations took place. Then, we walked out to the burial place where Sid and Matilda and two of their sons are buried. I remember in the fringe of the woods there was a large wisteria vine blooming. ‘Miss Ruth’ was a lovely lady to me and to my students. Over the next several years I visited her and she gave me permission to ramble over the battlefield. Visiting the Old Home Site One day, ‘Miss Ruth’ rode with us over to the site of the original house. At this time there were still stones lying loose from the foundation and a few shrubs around the door place. A more forlorn scene is hard to imagine. A long double row of yellow bulbs, jonquils and narcissus, ran on either side of the destroyed front entrance. A miasma of sadness hung over the whole place. From being a gracious home with love and laughter and children’s voices, the area had passed into history and legend.

| |||||||||||||

|

| Home | Grant's March | Pemberton's March | Battle of Champion Hill | Order of Battle | Diaries & Accounts | Official Records | | History | Re-enactments | Book Store | Battlefield Tour | Visitors | Copyright (c) James and Rebecca Drake, Margie Riddle Bearss, 2005. All Rights Reserved. |

Hiawatha

Hiawatha Billy Ellis got 'Miss Ruth’s' permission to dig up a few daffodil bulbs

for me but by that time I had moved to Arlington, Virginia. So, Billy

planted two of the bulbs in his yard and the other two in the yard of his

mother. The first season there were no blooms. The next season when they

did bloom - twisted withered-like stalks appeared instead of yellow

daffodils - and the blossoms resembled dead hands clawing at the sky. They

were so grotesque and evil appearing that Billy dug them up and destroyed

them. In later years, he wrote a poem called Champion Hill and dedicated

the poem to me. I was honored.

Billy Ellis got 'Miss Ruth’s' permission to dig up a few daffodil bulbs

for me but by that time I had moved to Arlington, Virginia. So, Billy

planted two of the bulbs in his yard and the other two in the yard of his

mother. The first season there were no blooms. The next season when they

did bloom - twisted withered-like stalks appeared instead of yellow

daffodils - and the blossoms resembled dead hands clawing at the sky. They

were so grotesque and evil appearing that Billy dug them up and destroyed

them. In later years, he wrote a poem called Champion Hill and dedicated

the poem to me. I was honored. From the outbreak of

the war, Matilda bore far more than her share of hardships. She was depended on to make dress clothes for Sid I as well

as relatives and friends -even while

she was attempting to feed her children

by raising the food, a job at which she was inexperienced and received little help from the slaves.

From the outbreak of

the war, Matilda bore far more than her share of hardships. She was depended on to make dress clothes for Sid I as well

as relatives and friends -even while

she was attempting to feed her children

by raising the food, a job at which she was inexperienced and received little help from the slaves.

The Champion House as it appeared during

Margie's

The Champion House as it appeared during

Margie's  Olivia Champion Birdsong, the wife of

Sid II, with her young son Sid S. III. Sid III was the heir to Champion Hill after the death of

Matilda in 1907. Photograph taken circa 1907.

Olivia Champion Birdsong, the wife of

Sid II, with her young son Sid S. III. Sid III was the heir to Champion Hill after the death of

Matilda in 1907. Photograph taken circa 1907.