|

The Defense of Vicksburg

Major S. H. Lockett, a native of Marion, Alabama, and a West Point graduate, served under General John Pemberton as chief engineer of the Department of Mississippi and Louisiana during the Vicksburg Campaign. On May 17th, during the battle of the Big Black River, Lockett destroyed the bridge over the river in order to stave off the enemy. Two decades after the war, the editors of Century magazine began to publish first hand accounts of major battles written by the leaders on both sides. The old editions of Century magazine have provided historians with some of the finest first hand accounts of the war. In 1956, with permission from Century magazine, many of the post-war articles were published in a four-volume series entitled Battles and Leaders of the Civil War. The article by Lockett, The Defense of Vicksburg, appeared in the volume entitled, Retreat from Gettysburg.

Excerpts from The Defeat at Champion Hill and Big

Black River Bridge Champion Hill: At last General Pemberton became convinced that General Grant’s intention was to march up the east bank of Big Black River, to strike the railroad at or near Edward’s depot, and thus cut his communications with Jackson. To prevent this, and at the same time to defeat Grant, if possible, he concentrated all of his forces at Edward’s depot, excepting General Forney’s division which was left in Vicksburg, and General Smith’s which was posted at and near the railroad bridge. On the 12th of May, under the orders of General Pemberton, I went to Edward’s depot to put the Confederate forces in position upon the ground selected for them to occupy, covering all the approaches from the south and east. The army here assembled consisted of three divisions: Bowen’s on the right, Loring’s on the center, and C. L. Stevenson’s on the left, numbering about 18,000 men. Some slight field-works had been thrown up at favorable points. The position was naturally a strong one, on high ground, the issue of which might have been different from that of the two unfortunate engagements which did actually occur. The army remained at Edward’s depot from the 134th to the 15th. During this time General Pemberton received numerous dispatches from President Davis, and from General J. E. Johnston, who had recently arrived at Jackson. I saw, or heard read, most of these dispatches. They were very conflicting in their tenor and neither those of Mr. Davis nor those of General Johnston exactly comported with General Pemberton’s views.

He then made the capital mistake of trying to

harmonize instructions from his superiors diametrically opposed to each

other, and at the same time to bring them into accord with his own

judgment, which was adverse to the plans of both. Mr. Davis’s idea was to

hold Vicksburg at all hazard, and not to endanger it by getting too far

from it. Johnston’s plan was to cut loose from Vicksburg altogether,

maneuver so as to avoid a general engagement with Grant until the

Confederate forces could be concentrated, and then beat him. Pemberton

wished to take a strong position on the line of the Big Black and wait for

an attack, believing that it would be successfully resisted, and that then

the tables could be turned upon Grant in a very bad position, without any

base of supplies, and without a well-protected line of retreat. Pemberton moved out from Edward’s depot in obedience to a dispatch from General Johnston, ordering him to attack in the rear a force which he supposed General Johnston was going to engage in front. Instead of this, he encountered Grant’s victorious army returning, exultant and eager for more prizes, from the capture of Jackson. Pemberton’s army, which was making a retrograde movement at the time, was put into the line of battle by being faced to the right with infantry, artillery, baggage, and ordnance wagons just as they were. In a few minutes after this disposition was made, his extreme left, previously the head of his column, was actively engaged with largely superior numbers. Under all circumstances the Confederates made a gallant fight, but they were driven from the field with heavy loss in killed, wounded, and captured, and a considerable loss of arms and ammunition. Stevenson’s division bore the brunt of the battle and suffered the heaviest losses. Bowen’s division sustained its reputation by making one of its grand old charges, in which it bored a hole through the Federal army, finding itself unsupported turned around and bored its way back again. Loring’s division did not cooperate with the other two, through some misunderstanding or misconception, and was scarcely engaged at all during the fight. Tilghman’s brigade of this division covered the road by which the Confederates retreated late in the afternoon. While in the discharge of this duty General Tilghman was killed. Big Black River Bridge: Our beaten forces, except Loring’s division, retreated across Baker’s Creek and took position at nightfall at Big Black Bridge; part of the forces, Bowen’s division and Vaughn’s brigade, being put in position in the tete-de-pont on the east bank of the river, and part on the bluffs on the west. Loring’s division was moved by its commander by the right flank, around the Federal army, and finally after a loss of most of its cannon and wagons, joined General Johnston at Jackson. The affair of Big Black Bridge was one an ex-Confederate participant naturally dislikes to record. The Federals engaged us early in the morning from a copse of woods on our left. I was standing on the railroad bridge at the time, and soon saw signs of unsteadiness in our men, and reported the fact to General Pemberton, received orders to prepare to destroy the bridges. Fence-rails and loose cotton saturated with turpentine were piled on the railroad bridge, and a barrel of spirits of turpentine placed on the steamer Dot, which was swung across the river and used as a bridge. About 9 o’clock our troops on the left (Vaughn’s brigade) broke from their breastworks and came pell-mell toward the bridges. Bowen’s men, seeing themselves unsupported, followed the example and soon the whole force was crossing the river by the bridges and by swimming, hotly pursued by the Federals. I was on the Dot at the time. Waiting until all the Confederates in sight were across the river, I touched a match to the barrel of turpentine, and with the aid of one of my lieutenants tipped it over. In a moment the boat was in a blaze. The railroad bridge was likewise fired, and all immediate danger of pursuit prevented. After the stampede at the bridge orders were issued for the army to fall back to Vicksburg, Major-General Stevenson being placed in command of the retreating forces. General Pemberton rode on himself to Bovina, a small railroad station about two and a half miles from the river. I was the only staff-officer with him He was very much depressed by the events of the last two days, and for some time after mounting his horse rode in silence. He finally said, "Just thirty years ago I began my military career by receiving my appointment to a cadetship at the U. S. Military Academy, and today - the same date - that career s ended in disaster and disgrace." I strove to encourage him, urging that things were not so bad as they seemed to be; that we still had two excellent divisions (Smith’s and Forney’s) which had not been engaged and were, therefore, fresh and not demoralized; that they could occupy our lines at Vicksburg, covering especially the approaches from the position now occupied by the Federal forces, which they would naturally follow; that the rest of the troops could be put, at first, in the less exposed parts of the line, or in reserve, until they had steadied themselves; that Vicksburg was strong and could not be carried by assault; and that Mr. Davis had telegraphed to him, "to hold Vicksburg at all hazard," adding that, "if besieged he would be relieved." To all of which Pemberton replied that my youth and hopes were the parents of my judgment; he himself did not believe our troops would stand the first shock of an attack.

We finally reached Bovina - here the general

halted and at my earnest insistence wrote an order directing me to return to

Vicksburg in all possible haste, to put the place in a good state of

defense.

Following the Battle of the Big Black River, Pemberton retreated into Vicksburg to try and prepare the Confederate forces for an attack. However, by this time man of the soldiers under his command had begun to think of him as a traitor and the general who "sold Vicksburg". Soldiers, as well as fellow officers had lost confidence in his leadership. After the retreat into Vicksburg, Pemberton sent a dispatch to General Johnston whose army had marched toward Canton, Mississippi, after the retreat from Jackson - then on toward the east banks of the Big Black River. Pemberton advised Johnston of the disaster at the Big Black saying, "the army has fallen back to the line of entrenchments around Vicksburg." He also informed Johnston of two disasters: that Loring’s division had disappeared and never made the crossing at the Big Black Bridge; and that Bowen had lost most of his artillery at the Big Black. On May 18th Pemberton received orders from Johnston to "abandon Vicksburg." Unable to follow Johnston’s order, Pemberton turned to his "council or War" and received a unanimous vote that "it was impossible to withdraw the army from this position with such morale and material as to be of further service to the Confederacy." Ignoring Johnston’s order, Pemberton sent a dispatch back to Johnston saying, "I have decided to hold Vicksburg as long as possible with the firm hope that the Government may yet be able to assist me in keeping this obstruction to the enemy’s free navigation of the Mississippi River. I still conceive it to be the most important point in the Confederacy." Vicksburg fell to the enemy on July 4, 1863, and Pemberton would forever bear the shame of being the general who lost the war. After the war, a long going feud erupted between Johnston and Pemberton, each blaming the other for the loss of Vicksburg. The feud and the blame game would last for the remainder of their lives. Rebecca Blackwell Drake

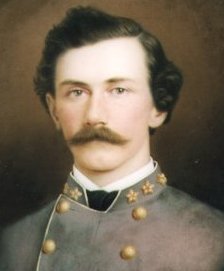

Samuel Lockett was born in Mecklenburg County, Virginia, on July 7, 1837. He was the son of Napoleon Lockett and Mary Clay Lockett. Samuel grew up in Marion, Alabama, where he attended Howard College. In 1859 he graduated second in his class from the U.S. Military Academy at West Point and he married Cornelia Clark. During the Civil War he served as an engineer with the Confederate Army, rising to the rank of colonel and chief engineer of the Army of Tennessee. Nicola Marschall served as one of his draftsmen. After the war Lockett taught in Louisiana and Alabama, and later at the University of Tennessee. He was a prolific writer and artist. From 1875 to 1877 he served with the Egyptian army. Lockett also served as principal assistant engineer in the construction of the pedestal for the Statue of Liberty. He was assigned to Chile in 1888 to work on a massive construction project. He died on October 12, 1891, in Bogota, Colombia. Biographical Sketch and Photograph Courtesy

of Alabama Department of Archives and History |

|

| Home | Grant's March | Pemberton's March | Battle of Champion Hill | Order of Battle | Diaries & Accounts | Official Records | | History | Re-enactments | Book Store | Battlefield Tour | Visitors | Copyright (c) James and Rebecca Drake, 1998 - 2007. All Rights Reserved. |